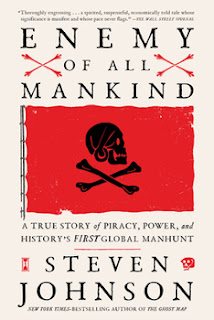

Enemy of All Mankind

The book in PDF at My Google Drive

The book delves into the history of piracy, beginning with the Sea Peoples of the ancient world, exploring the origins of piracy and its evolution over centuries. It discusses the role of pirates in the global imagination and their impact on commerce, culture, and international law.

A significant portion of the summary explores the economic implications of piracy and the specific event involving Avery. It examines the intricate relationships between pirates, global trade, cultural perceptions of piracy, and the media's role in shaping the image of pirates.

The Mughals and Global Trade: The narrative also provides a detailed account of the rise of the Mughal Empire, its economic prowess, and its significance in global trade, particularly highlighting the importance of cotton and the subcontinent's wealth.

chapter 1 Origin stories

The first chapter titled "Origin Stories" in the book "Enemy of All" covers the beginning of a journey that intertwines historical narratives and personal ambitions. It begins with a vivid depiction of the events of September 1695, highlighting a dramatic encounter on the Indian Ocean near Surat. This moment is presented as a culmination of various historical threads: the accumulation of Indian wealth over centuries, the pilgrimage routes defined by Muhammad, the power of the Mughal empire under Aurangzeb, and the precarious situation of the East India Company. The chapter emphasizes the convergence of these diverse narratives through the lens of 200 men on a ship, far from home, low on supplies, and driven by the desire to amass fortune.

This chapter seems to set the stage for exploring the profound impacts of a pivotal moment in history, where personal ambitions clash with the grand narratives of empires and trade. It suggests an intricate web of causes and effects, where the actions of individuals on the global stage resonate through the annals of history. The detailed exploration of these events and their broader implications promises to offer insights into the complexities of human endeavor, ambition, and the inexorable march of history.

Chapter 2 "The Uses of Terror,"

The Chapter explores the historical evolution of terror as a strategic tool, drawing parallels between piracy and modern terrorism. The chapter begins by discussing the strategic use of terror by pirates in asymmetric warfare, allowing smaller forces to challenge much larger ones successfully. It highlights how piracy shares many traits with modern terrorism, including its impact on the popular imagination and its legal definition. The chapter traces the etymology of "terrorism" back to the French Revolution, initially a tactic of the state, and its shift to being associated with non-state actors like anarchists and insurgents in the twentieth century.

The narrative details how modern terrorism, unlike the state-monopolized terror of the past, empowers small groups to instill fear among larger populations without needing substantial military resources. This change is a form of asymmetric warfare where acts of terror by non-state actors can have disproportionate effects, facilitated by media dissemination. The chapter also touches on the historical instances of terror, including the brutal actions of pirates and their impact on societies and governance. It discusses how these early forms of terror laid the groundwork for contemporary terrorism's strategies and objectives, emphasizing the shift from state-directed terror to the non-state, insurgent-led terror that characterizes much of modern conflict.

This analysis provides a comprehensive overview of the chapter, underscoring the complexity of terror as a concept and its evolution from a tool of state power to a strategy employed by non-state actors to challenge established authorities and disrupt societies

Chapter 3 " THE RISE OF THE MUGHALS"

'Chapter 3, "The Rise of the Mughals," delves into the historical backdrop of the Mughal dynasty's establishment and its implications on the Indian subcontinent and beyond. This chapter outlines the foundational events leading to the Mughal Empire's dominance, starting from the early Islamic incursions into India, which paved the way for a series of military and cultural shifts that would eventually culminate in the rise of one of history's most influential empires.

The narrative begins with the early Muslim traders and conquerors who ventured into India, setting the stage for a long period of Islamic rule over various parts of the region. This period saw a blend of conflict and coexistence between Hindu and Muslim cultures, with significant contributions to India's social, cultural, and economic fabric. The chapter highlights the key figures and moments in the establishment and expansion of the Mughal Empire, including the notable rulers who shaped its destiny.

A significant focus is on the grandeur and governance of the Mughal rulers, particularly the most renowned among them, such as Babur, who laid the empire's foundations, Akbar, whose policies of religious tolerance and cultural synthesis left a lasting legacy, and Aurangzeb, whose reign marked both the zenith of Mughal territorial expansion and the beginning of its decline. The narrative weaves through the complexities of Mughal succession, the empire's administrative and military innovations, and its role in global trade, especially in luxuries like cotton and spices that attracted European interest.

The chapter also addresses the cultural and architectural achievements of the Mughals, their impact on the Indian subcontinent's social fabric, and the eventual challenges that led to the empire's decline. It sets the stage for understanding the intricate dynamics of power, culture, and economy that defined the Mughal era, providing a comprehensive view of how this period shaped the course of Indian history and its interactions with the wider world.

Global trade ultimately made India too wealthy for Islam’s imperial ambitions to resist. From 1 CE to 1500 CE, no region in the world— including China—had a larger share of global GDP. Its copious supply of pearls, diamonds, ivory, ebony, and spices ensured that India ran what amounted to a thousand-year trade surplus. But no product ignited the imagination of the world—and emptied its pocketbooks—like the dyed cotton fabrics that would play such a critical role in the history of India

By the end of the millennium, that shipping network would be run almost exclusively by Muslim traders. The result was a geoeconomic system in which an artisanal Hindu society produced valuable goods, while surrounded by a membrane of Islamic merchants and sailors concentrated in the harbor cities that allowed those goods to circulate on the world market.

The question of why India itself never developed its own trade networks leads to one of the great “what if” thought experiments of global history. Had the subcontinent’s combination of immense natural resources and technical ingenuity been matched with an equivalent appetite for seafaring trade, it is not hard to imagine India following the path to industrialization and global dominance before England made its great leap forward economically in the 1700s. One explanation for India’s reluctance to trade lies in the Hindu prohibition against oceanic travel. According to the Baudhayana sutra, anyone “making voyages by sea” would lose their status in the caste system, a punishment that could only be absolved through an elaborate form of penance: “They shall eat every fourth mealtime a little food, bathe at the time of the three libations (morning, noon and evening), passing the day standing and the night sitting. After the lapse of three years, they throw off their guilt.” The prohibition itself took only a few lines to spell out, but it cast a long shadow

Chapter 4 "Hostis Humani Generis"

Comments

Post a Comment